Bad Idea: Overclassification

The overclassification of information poses a serious problem for national security. Restricting access to information prevents timely analysis and impedes decision-making by limiting debate on key policy issues to small groups of people within the government, and it inhibits public scrutiny of classified information and the decisions made from it. While it is critical to protect sensitive sources and methods, much of the information gleaned from these sources can still be made available in declassified formats. Still other information is already, and should properly be kept, in the public domain. Secrecy is inconsistent with the fundamental principles of transparency and democratic accountability, and the perception that government officials are using it to hide their own malfeasance contributes to widespread public disillusionment.

A Brief History

Generally speaking, government agencies are interested in preventing unauthorized disclosure of sensitive information, and they often err on the side of security over transparency. Sometimes, however, senior leadership can break the log-jam. President Bill Clinton’s Executive Order 12958, for example, automatically declassified documents more than 25 years old, “unless the Government took discrete, affirmative steps to continue classification.” In the wake of EO 12958, the governing presumption was that the government could only withhold information if it made a compelling case for secrecy.

Following the 9/11 attacks, however, President George W. Bush directed White House Chief of Staff Andrew Card to draft new guidelines governing what information would be shielded from public view. The so-called “Card memo” directed government agencies to withhold access to sensitive material and to entertain formal requests for public access to information under the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) only when “there was a sound legal basis to do so.”

Ironically, only two years after the “Card Memo” was issued, the 9/11 Commission report sharply criticized the very “close hold” mentality reflected in the memo and the general mindset among national security bureaucrats that compromised efforts to prevent the attacks:

The culture of agencies feeling they own the information they gathered at taxpayer expense must be replaced by a culture in which the agencies instead feel they have a duty to the information—to repay the taxpayers’ investment by making that information available.

The Obama administration entered office in 2009 promising “the most transparent Administration in history,” but by the beginning of Obama’s second term, journalists and government transparency advocates found their hopes for greater transparency dashed. In October 2013, former Washington Post executive editor Leonard Downie complained that the Obama administration’s “war on leaks and other efforts to control information are the most aggressive I’ve seen since the Nixon administration.” Obama’s administration would set new records for taxpayer money spent to deny Americans’ access to government records.

The Effects

The practical effects of these actions over the years have been enormous. Documents that have always been unclassified have been newly classified. Documents that were declassified in whole or in part have been reclassified. Meanwhile, all new information obtained and created within the federal government has been subjected to a standard that elevates secrecy above openness at virtually every step of the way.

The problem goes well beyond those documents marked as “classified.” Designations such as “For Official Use Only,” “Sensitive But Unclassified,” and “Limited Official Use,” can all be used to block the release of information. This leads to widespread abuse.

An ongoing FOIA lawsuit against the Defense Department Inspector General (Eddington v DoD IG, 17-cv-0012) illustrates the point. One of the authors (Eddington) is seeking the declassification of, among other documents, a December 2004 DoD IG audit report that was sharply critical of a failed National Security Agency (NSA) digital network exploitation program code named TRAILBLAZER. A highly redacted version of the report was released to the Project on Government Oversight in 2011, but the NSA has repeatedly invoked PL 86-36, Section 6 to prevent the disclosure of DoD IG auditor comments and findings that were damning of NSA’s handling of the TRAILBLAZER program, and a far superior, rival program code named THINTHREAD.

Thanks to the efforts of the Chicago law firm of Loevy & Loevy, Eddington has succeeded in getting substantially more of the report declassified, and a side-by-side comparison of just one example of the NSA’s misuse of PL 86-36 is below.

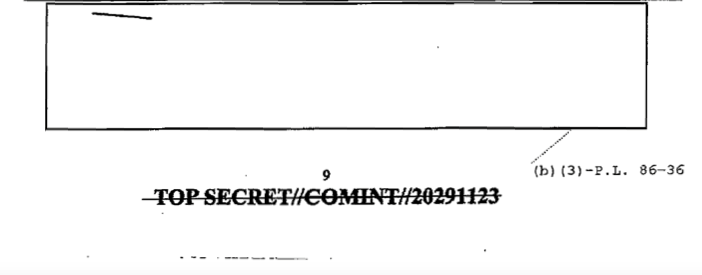

DoD IG report extract, p. 9, 2011 version:

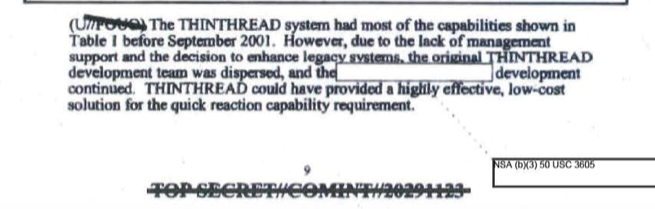

DoD IG report extract, p. 9, 2017 version:

Note that the paragraph that was entirely redacted until Eddington’s litigation was itself not classified. The designation “U/FOUO” is shorthand for “Unclassified—For Official Use Only” and nothing in the paragraph was or should be classified or otherwise withheld from public release. The NSA’s continued concealment efforts appear to be aimed at avoiding further embarrassment for the agency, not protecting legitimately classified sources and methods.

Overclassification and other practices have also been used to conceal critical historical facts from the American people. Despite more than 50 years having passed since the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., at least 17,000 pages of FBI records on King remain classified. Indeed, Eddington’s research has discovered that if the case file boxes holding FBI records in the “Domestic Security” category from 1939 to 1984 were laid end-to-end, they would stretch for almost seven miles.

How many Americans were improperly spied upon by the FBI during this period? We have no idea. The key reason we can’t answer that question is that those FBI “Domestic Security” records have technically been declassified but not reviewed under FOIA for release. This means that the records remain well out of the public’s reach.

The Costs

The practice of withholding data from the American public isn’t cheap. As of 2012, the costs of classifying and storing some 95 million documents for a single year was estimated at $10 billion. Presuming that most of those materials do not contain information about a CIA covert agent or a sensitive code-breaking technique, it is reasonable to surmise that a considerable portion of this $10 billion is simply wasted. Other costs are borne by the private sector, or passed along to taxpayers. For example, contractors doing work for the government typically have to hire cleared workers (who can demand higher pay), and maintain cleared facilities. The need to move between classified and unclassified environments also undermines worker productivity.

Another cost can’t easily be measured: growing cynicism about the government. Americans tell pollsters that government officials hold back things the public has a right to know. Whether the revelations have come from individuals like Edward Snowden, or from one of the thousands of federal FOIA lawsuits filed every year, each time federal officials are caught concealing embarrassing or criminal behavior, it feeds public distrust of government officials and institutions. Simply stated, secrecy is poisonous to democracy.

Conclusion

The belief that limiting access to most information makes us safer is a fallacy; the opposite is probably closer to the truth. There will always be some risk that sensitive information will fall into the wrong hands. As it is today, however, there is even greater risk that actionable intelligence will not fall into the right hands; in many cases, those right hands may actually be the wider public, men and women who have no other reason to possess a security clearance, but who do have subject matter expertise. The burden of proof should therefore fall on those attempting to conceal information from the public. If they don’t loosen the restrictions, our unique strengths as a nation – our openness, tolerance, educational freedom, and cultural diversity – will remain underutilized. Meanwhile, continuing to shroud government actions behind a veil of secrecy will only deepen the divide between that government and the people it is supposed to serve.

(Photo Credit: National Security Archive, George Washington University)