What the Continuing Resolution Means for Defense Spending in FY 2018

On September 8, President Trump signed into law H.R. 601, the “Continuing Appropriations Act, 2018 and Supplemental Appropriations for Disaster Relief Requirements Act, 2017.” The bill addresses several timely concerns, providing $15.25 billion in emergency funding for disaster relief, temporarily suspending the federal debt ceiling, and funding the federal government with a continuing resolution (CR) that runs through December 8. Below are five critical questions asked and answered about the continuing resolution and its impact on the FY 2018 defense budget.

Q1: What does the continuing resolution include?

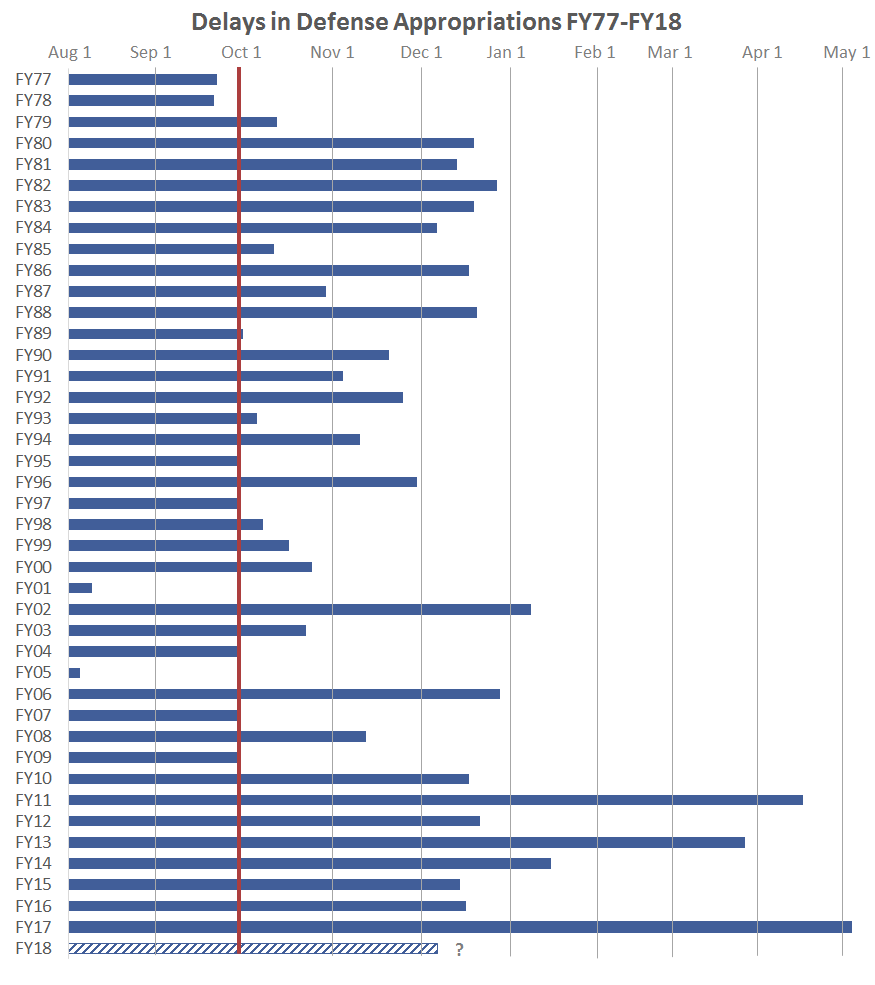

A1: The continuing resolution included in H.R. 601 is part of an agreement reached by the administration and congressional Democrats to avoid breaching the debt ceiling, to provide disaster relief funding, and to prevent a government shutdown. The odds Congress would pass a defense appropriations bill by October 1, 2017, the start of the new fiscal year, were low from the outset given that defense has started the fiscal year under a CR for 79 percent of the years since the start of the fiscal year was moved to October 1 in FY 1977.

The CR prevents a government shutdown and gives Congress more time to reach a budget agreement, likely raising the caps for both the defense and nondefense sides of the budget. Without an agreement to raise the budget caps, the base defense budget will be limited to slightly below the FY 2017 level regardless of what Congress ultimately appropriates. The decision to tie the CR and debt ceiling increase to urgently needed disaster relief helped ease its passage and likely avoided a fiscal standoff at the end of September.

The CR provides funding for federal programs at the FY 2017 appropriation levels through December 8, 2017. The funding level for national defense is $551 billion in the base national defense budget with an additional $83 billion in Overseas Contingency Operations (OCO) funding for a total of $634 billion. But the CR also includes an across-the-board reduction of 0.6791 percent that applies only to the base budget, bringing the effective annualized level for national defense to $547 billion in the base budget and $630 billion in total national defense. Some leaders in Congress and in the Pentagon wanted to include “anomalies,” or exceptions in the CR that would increase funding for specific priorities—missile defense, military personnel, and readiness expenses for Thornberry and new-start acquisition programs for the Department of Defense (DoD)—but those requests were not accepted by the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) and not included in the bill. Including such exceptions in the CR would have lessened the immediate detrimental effects, but in the long run this could make a CR more politically palatable and lessen the pressure on Congress to pass a full-year appropriations bill.

Q2: How does this CR compare with past CRs?

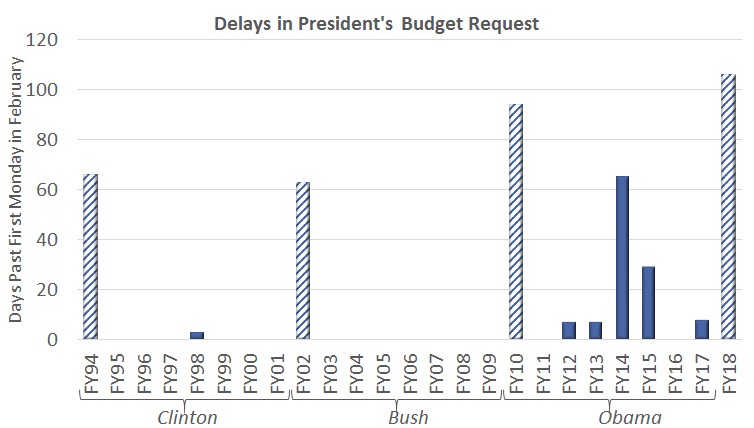

A2: Starting the fiscal year with a CR has become normal. In the last 42 years, defense has started the fiscal year under a CR 33 times. Or as DoD comptroller David Norquist recently put it, “Just another sign of fall, the kids go back to school, football season begins and the federal government operates under a CR.” But if the Trump administration wanted to push Congress to pass a complete budget on time, its decision to submit its budget request on May 23 certainly did not help. While it is normal that the budget request in the first year of a new administration is released later than usual (the first Monday in February), the Trump administration’s first budget request is the latest in recent history, coming in 106 days after Monday, February 6. It surpasses the request in the first year of the Obama administration—also historically late—by 12 days.

The CR for FY 2017 was the longest CR for defense since the Budget Act of 1974 changed the start of the fiscal year from July 1 to October 1. In the Fall of 2016, the Republican leadership in Congress, at the urging of the incoming Trump administration, enacted a long-term CR to fund the government rather than try to pass appropriation bills during the lame-duck session in late 2016. Senator John McCain (R-AZ) vociferously opposed the measure at the time, saying the CR would “do great damage to the military and our ability to defend the nation.” Ultimately, the government operated under a CR for a total of 217 days (roughly seven months) in FY 2017 under three successive continuing resolutions that lasted until May 5.

Q3: Will the CR trigger sequestration?

A3: The Budget Control Act (BCA) caps in effect for FY 2018 currently sit at $549 billion for defense, approximately $2 billion below the FY 2017 base defense funding level of $551 billion provided in the CR. Hypothetically, this would violate the BCA budget caps and trigger sequestration. However, Section 101(b) of Division D in H.R. 601 details that the “rate for operations provided [in the bill] is hereby reduced 0.6791 percent.” This reduction decreases the base defense budget topline by roughly $4 billion to $547 billion on an annualized basis. Consequently, the current CR does not violate the budget caps. Sequestration is also not triggered under the Budget Control Act until 15 days after the end of the current session, which will be January 15, 2018. The current CR expires on December 8, 2017, meaning that under current law the CR will no longer be in effect by the time a sequestration could be triggered.

| Budget Function

(discretionary budget authority in current dollars) |

FY 2017 Funding Levels

|

FY 2018 Continuing Resolution Funding Levels

(base reduced by 0.6791 percent) |

Trump FY 2018 Request

|

| National Defense (050) Base | $551.1 B | $547.4 B | $603.0 B |

| National Defense (050) OCO | $82.9 B | $82.9 B | $64.6. B |

| National Defense (050) Total | $634.0 B | $630.3 B | $667.6 B |

| BCA Budget Cap for 050

(applies to base only) |

$549.1 B | $549.1 B | $549.1 B |

| Amount Over the BCA Caps | +$2.0 B | -$1.7 | +$53.9 B |

Q4: How will the CR impact national defense?

A4: The continuing resolution generated significant opposition from the leadership of the respective House and Senate defense committees, who claimed it would harm national security. Representative Mac Thornberry (R-TX), for example, voted against the bill even though it provided emergency relief to his home state of Texas after the destruction caused by Hurricane Harvey. Senate Armed Services Committee chairman McCain joined his counterpart in voting against the bill, later explaining “[T]his agreement basically freezes last year’s funding in place, which is a cut of $52 billion.” McCain, however, mischaracterizes the CR in describing it as a “cut.” It is a cut relative to the requested level of $603 billion for the FY 2018 base budget, but it is only a minor reduction ($4 billion) from the current level of funding. The CR also continues the $83 billion in OCO funding, which is $18 billion more than the OCO funding DoD requested for FY 2018. Although OMB is unlikely to let DoD spend at that level during a short CR, the money would be there in the event of a full-year CR.

The Pentagon has repeatedly expressed its displeasure with being forced to operate under a CR. In a letter to McCain, Secretary of Defense James Mattis explained the impacts of operating under a CR, particularly those related to readiness and maintenance. They include:

- Scaled-back training exercises across the services

- The delayed induction of 11 ships by the Navy

- The postponement of all “noncritical” maintenance work orders by the Army

- The curtailment of hiring and recruitment

- Rising acquisition costs from severed contracts and renegotiated terms due to the CR

One of the most significant areas impacted by the CR is in new-start acquisition programs, which, along with production rate increases, cannot begin while a CR is in effect. In a list DoD sent to OMB, approximately 75 new-start programs are cited across the services that would not be able to proceed as planned under a CR. As Mattis notes, “the longer the CR, the greater the consequences for our force.” If Congress extends the CR significantly past December 8, DoD would likely request that it include some exceptions for new-start programs, as it has done in the past.

The terms of the CR similarly state that advanced procurement funding cannot be spent to initiate multiyear procurement contracts, which DoD uses to reduce costs by contracting for multiple years’ worth of procurements at once. For example, the Navy cannot proceed with the planned multiyear procurement of 10 Arleigh Burke–class guided-missile destroyers from FY 2018 to FY 2022 as planned in the FY 2018 budget request while the CR is in effect.

A broader effect of a CR is that funding is locked into all of DoD’s accounts at the levels appropriated last year. Since funding needs naturally vary from year to year across accounts, this means that some accounts may be short of funding while others have excess funding in the new fiscal year. Though the lasting effect of a short-term CR may be limited, long-term CRs can have a much more significant impact on DoD. Accounts that are below their desired level under a longer CR will be forced to spend at a lower rate, which can limit the number of personnel, maintenance, training, and other activities that can take place while the CR is in effect.

Q5: What are the range of outcomes for this year’s defense budget?

A5: There are four main options for how the defense budget debate will play out this year:

- Congress reaches a budget deal in December.

One possibility is that Congress will reach a deal to raise the BCA caps and pass appropriations bills before December 8. The House already passed a defense spending bill at the end of July for $614 billion in base discretionary funding (including military construction and atomic energy funding) plus an additional $74 billion in OCO. The Senate has not yet passed a defense appropriations bill. If the House bill is enacted as written, it would be $65 billion above the BCA budget cap for defense in FY 2018 and would trigger a sequester cutting it back to the budget cap level. Thus, any appropriations bill that exceeds the budget cap will need to be accompanied by a broader budget deal that alters the budget cap levels or moves more funding from the base budget into the OCO budget.

Many in Congress, particularly, defense hawks, have called for more lasting legislation that eliminates the budget caps and the limits imposed on defense spending. Such action would undoubtedly lead to conflict with fiscal hawks looking to limit all federal expenditures and lower the deficit. Senator Tom Cotton (R-AR) offered an amendment to the Senate defense authorization bill that would have eliminated the enforcement of the BCA budget caps by sequestration, effectively rendering them moot. However, this amendment ultimately failed. Since 60 votes are needed in the Senate to raise or eliminate the budget caps, any deal will need to be bipartisan. In the past, that has meant increases in both the defense and nondefense sides of the budget caps. But given Republicans’ control of both chambers of Congress and the White House, a new deal may result in higher increases for defense than nondefense. The FY 2017 budget agreement reached in May under the Republican Congress provides an early example; while the base budget remained at the BCA cap levels for both defense and nondefense, a greater level of OCO funding was allocated to defense programs than to nondefense programs.

- Congress punts into the New Year.

Given that the length of CRs over the past eight years has averaged more than four months, it would not be surprising if Congress extended the current CR. It could extend the CR into January or February to provide more time to negotiate an agreement on the BCA caps. If such an agreement is eventually reached, Congress would then need to pass regular appropriations bills that conform to the revised budget caps.

- Congress passes a full-year CR.

If Congress is ultimately unable to reach an agreement to raise the budget caps, the result could be a full-year CR. Ranking member of the House Armed Services Committee Adam Smith (D-WA) believes that is the fate of the FY 2018 budget process, saying, “We are headed towards a complete meltdown at the end of this year.” Smith is not optimistic about an agreement over the budget caps, believing that House Republicans who recently passed a defense appropriations bill in violation of the caps will not agree to raise nondefense funding levels. To the ranking member, passing a year-long CR would be “borderline legislative malpractice” and lead to significant opposition from the Department of Defense and congressional defense hawks. It is worth noting, however, that defense has never experienced a full-year CR, and Republican leaders remain optimistic that an agreement can be reached.

- Government shutdown.

If Congress fails to negotiate a deal on the budget caps and cannot pass an extended CR, the result would be a government shutdown. While this outcome seems unlikely at present, President Trump has openly mused about it in the past. In May, the president tweeted that “the country needs a good ‘shutdown’ in September to fix mess” and later suggested he would let a shutdown occur if a border wall was not funded. While a government shutdown would be highly disruptive for the Department of Defense, previous government shutdowns have ultimately led to budget deals. The shutdown that occurred at the beginning of FY 2014, for example, was followed by a deal that raised the budget caps for defense by $22.5 billion in FY 2014 and $9.3 billion in FY 2015.

Seamus Daniels is program coordinator and research assistant for Defense Budget Analysis at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) in Washington, D.C. Todd Harrison is a senior fellow and director of Defense Budget Analysis at CSIS.

Critical Questions is produced by the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), a private, tax-exempt institution focusing on international public policy issues. Its research is nonpartisan and nonproprietary. CSIS does not take specific policy positions. Accordingly, all views, positions, and conclusions expressed in this publication should be understood to be solely those of the author(s).

© 2017 by the Center for Strategic and International Studies. All rights reserved.