Nuclear Modernization under Competing Pressures

Transition46 Series

The Biden administration will face early decision points regarding the modernization of critical elements of the U.S. nuclear weapons enterprise in an environment buffeted by competing forces and pressures. Fiscal constraints and a highly competitive budget climate, allies and partners seeking reassurance as to U.S. commitments to collective security, and a complex political climate for arms control and nonproliferation dynamics all pose significant challenges for the new administration.

Q1: What are the biggest challenges facing nuclear modernization?

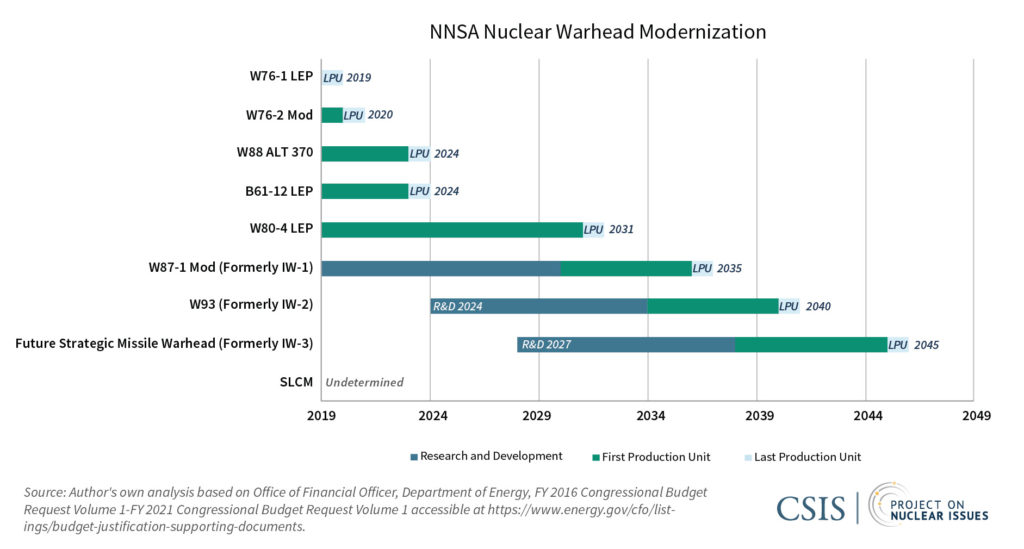

A1: The Biden administration will face high-priority, high-profile decision points for nuclear modernization early this spring, and it will likely be contentious as stakeholders within and outside of government are already positioning publicly on a range of topics. Currently, there are ongoing efforts in the Department of Defense (DoD) and the National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) to modernize nearly every aspect of the U.S. nuclear arsenal over the next two decades. This includes all three legs of the nuclear triad and their associated delivery systems, an overhaul of the nuclear command and control architecture, the replacement of the air-launched cruise missile (ALCM) with the long-range stand-off weapon (LRSO), and a range of warhead modernization and refurbishment efforts. Additionally, NNSA plans to produce at least two new warheads for the stockpile: the W93 and the Future Strategic Missile Warhead.

In confirmation testimony both Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin and Deputy Secretary of Defense Kathleen Hicks expressed general support for nuclear modernization and the nuclear triad, but they did not commit to specific programs, procurements, or schedules. The devil is always in the details, however, and it is in those details where these issues will come to a head early in the administration. Other appointees in the new administration have long-standing objections to central aspects of the existing program of record, especially the LRSO, Ground Based Strategic Deterrent (GBSD), and NNSA’s warhead modernization and production efforts. We can, and should, expect a thorough scrubbing of these programs for cost, efficiency, and schedule within DoD and on policy grounds in broader interagency debate.

Support is mixed on Capitol Hill as well. House Armed Services Committee (HASC) chairman Adam Smith (D-WA) has long voiced personal reservations about some nuclear modernization programs, particularly the GBSD. Yet overall, congressional support for the existing nuclear modernization program has remained consistent over the past half-dozen National Defense Authorization Acts (NDAA). Speaking at CSIS on December 11, 2020, Chairman Smith made it clear that he expected many of these programs to continue to enjoy strong support on Capitol Hill. The FY 2021 NDAA and appropriations bills bear that out, as all the key elements of modernization are fully—or nearly fully—funded. The next test for these programs will come as the new administration prepares to submit its FY 2022 defense budget in early spring. With the long-awaited “bow wave” of expenditures now underway, it will be difficult to delay many of the critical funding decisions on major programs until after a full nuclear posture review can be completed.

The nuclear modernization debate will continue to unfold in a climate of deep ideological polarization across the nuclear policy landscape. Finding middle ground is possible but it will take a willingness from across the community to lower the temperature and calm the rhetoric while the new administration reviews the options and determines a path forward.

Q2: What element of modernization is likely to face the most scrutiny and debate?

A2: The GBSD and its corresponding W87-1 warhead is one modernization program that will face rigorous scrutiny in the early stages of the Biden administration. The GBSD is scheduled to replace the aging Minuteman III intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) in the latter part of this decade. First fielded in 1970, the Minuteman III is the only land-based nuclear weapon in the U.S. nuclear triad.

Opponents believe that the GBSD is excessively expensive and unnecessary because of the United States’ highly survivable submarine-launched ballistic missile (SLBM) force. They also argue and that its permanent alert status increases risks of accidental or miscalculated nuclear use. Proponents of GBSD emphasize that the ICBM leg ensures that no U.S. adversary can consider a disarming first strike without committing to a large nuclear attack deep in U.S. territory—thereby significantly raising the nuclear threshold for an adversary. Because the air leg of U.S. nuclear forces—which today includes the dual-use B52s and the B2 (and future B21)—is no longer on continuous alert, the United States would be solely dependent upon the submarine leg for any prompt nuclear response in the absence of a ground-based nuclear force. Such a change would have far-reaching implications for overall U.S. nuclear posture, including alert status, readiness requirements, targeting, and weapon allocation and distribution. A complete analysis of these requirements will be difficult to complete in the first months of the administration.

Recognizing these challenges, a number of GBSD opponents have proposed further life extension options for the Minuteman III. By reducing testing rates and reducing the number of deployed missiles from 400 to a lower number, they argue, the United States could buy time and delay final decisions on a costly replacement. Many such proposals, however, fail to account for how life extension for the Minuteman missiles can be decoupled from essential upgrades to the system of missile launch facilities and launch control centers that must be fully integrated with ongoing nuclear command, control, and communications (NC3) infrastructure modernization efforts. NC3 modernization enjoys bipartisan support in Congress and the broader nuclear policy community given concerns about future cyber resiliency. U.S. military leadership has been quite vocal in opposition to such life extension proposals for the 50-year-old system. Most notably, in a January 5, 2021 call with the Defense Writers Group, Admiral Charles Richard, Commander of U.S. Strategic Command, stated, “You cannot life-extend the Minuteman III.”

Last year, HASC vigorously debated transferring funding from GBSD to Covid-19 pandemic relief. Ultimately, however, HASC approved $1.5 billion for GBSD in FY 2021 and received nearly full funding in the final NDAA. While GBSD remains a contentious issue among some in Congress, supporters continue to have the upper hand for now. Additionally, the program is widely supported by senior leadership in DoD. In recent months, several military leaders have spoken publicly in favor of maintaining the full nuclear modernization program of record. Regardless, given this highly polarized climate, funding and broader policy support for GBSD will likely be a contentious issue in the months ahead.

Q3: What is an unforeseen or underappreciated challenge facing U.S. nuclear modernization?

A3: In the modernization debate, the high-profile, high-dollar strategic delivery systems get most of the attention, but they are by no means the only issues on the nuclear modernization plate. One underappreciated challenge is the effective modernization of the U.S. nuclear stockpile itself. These issues include sustaining complex life extension and warhead modernization programs, ensuring that the United States can produce weapons as needed well into the future, and maintaining a viable supply chain for critical components such as tritium.

One example well illustrates this challenge. A handful of U.S. nuclear warheads may require newly produced plutonium pits to ensure that they continue to function to the end of the century. Plutonium pits have an estimated lifespan of 80–90 years. This requirement applies to the W87-1 and may apply to the W93, the Future Strategic Missile Warhead, and submarine-launched cruise missile warhead. To support nuclear-warhead modernization projects, the United States currently plans to produce 80 pits per year by 2030 at two sites: Los Alamos National Laboratory in New Mexico and the Savannah River Site in South Carolina. The United States has not operated a full-scale plutonium pit production facility since 1989, and some in the nuclear policy community are highly skeptical about the project’s feasibility and cost profile.

NNSA’s schedule for the expansion of Los Alamos and construction at the Savannah River Site has been called overly ambitious by analysts at federally funded research and development centers. In 2019, the Institute for Defense Analyses (IDA) released a report evaluating NNSA’s two-site solution for plutonium pit production and questioning the expected timeline for the Savannah River location. It noted that “IDA examined past NNSA programs and could find no historical precedent to support starting initial operations by 2030, much less full rate production.” IDA assessed that the plans for the Savannah River Site were likely to experience substantial cost growth and schedule slippage—and could even be completely canceled. It also questioned whether Los Alamos could meet its goals by 2030.

Q4: How is U.S. nuclear modernization connected to the recommitment to U.S. alliances?

A4: The Biden administration has committed to a national security policy that works by, with, and through our allies and partners around the world. For those allies that rely on U.S. nuclear guarantees in the form of extended deterrence—most notably North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) allies, Japan, South Korea, and Australia—U.S. nuclear policy and posture is inextricably linked to their own security requirements. These relationships cut both ways. The U.S. system of allies and partners around the world provides the most potent, and often underappreciated, element of U.S. deterrence posture: an element that has endured considerable strain over the last several years. Those partners have strong views and concerns about U.S. nuclear posture: They strongly favor a return to serious arms control and dialogue on the one hand, but also hold deep reservations about changes to U.S. programs and posture that could undermine or appear to undermine the U.S. commitment to extended deterrence. Ensuring U.S. commitment to key allies will require robust and tailored consultations and a real commitment to listening. Issues such as sustaining the nuclear triad, the presence of U.S. nuclear capabilities in Europe, pressure for multilateral arms control that includes the United Kingdom and France, reductions in lower-yield nuclear options intended to address deterrence gaps in regional conflicts, and other pressing issues should not be seen as decisions for the United States alone to make—if indeed our commitment to partnership and alliance cohesions is more than just empty words. Moreover, unilateral cutbacks on nuclear modernization may also strain U.S. alliances while also undermining the U.S. ability to further engage in meaningful arms control by presumptively reducing its bargaining power for the negotiations ahead.

Another underappreciated alliance issue involves the replacement delivery platform and warhead for the Trident SLBM, which the United States and United Kingdom are building concurrently. By committing to a “new” warhead (the first newly numbered U.S. nuclear warhead since 1992), the Trump administration raised the profile and the stakes for the new warhead and injected considerable controversy into the program. Canceling that missile or the missile’s W93 warhead could have serious implications for the United Kingdom’s ability to meet its own modernization timelines and may erode more than 60 years of cooperation between the two countries under the 1958 U.S.-UK Mutual Defense Agreement. The UK government has reportedly lobbied members of the U.S. Congress to support the W93 program.

Determining and mitigating the ripple effects of policy options across alliances, modernization, and arms control will be crucial to ensuring a successful U.S. nuclear weapons modernization program and producing effective wider nuclear policy outcomes. This will take time to engage in full and transparent consultations and a recognition of the need to compromise to create safer, enduring deterrence relationships with our allies.

Q5: How is U.S. nuclear modernization impacting international nuclear nonproliferation?

A5: The Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT) remains the cornerstone of the global nuclear nonproliferation regime and its three pillars—obligations that prevent the proliferation of nuclear weapons, commit states to pursue disarmament, and ensure that the safeguarded, peaceful uses of nuclear energy form the backbone of nuclear nonproliferation efforts and nuclear cooperation. Under Article VI of the NPT, signatories pledge to pursue “effective measures relating to cessation of the nuclear arms race at an early date and to nuclear disarmament, and on a treaty on general and complete disarmament under strict and effective international control.” In recent years, the NPT has come under increasing strain. Resentments among non-nuclear weapons states that the United States and the four other treaty-designated nuclear weapon states have failed to live up to their disarmament obligations run deep, especially after four years of backsliding across a range of arms control issues. Additionally, all five recognized nuclear weapon states are currently modernizing their nuclear arsenals, prompting fears of arms racing and a perception that risks of nuclear war are rising rather than declining.

Meanwhile, some non-nuclear weapon states have negotiated and brought into force the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TNPW), which declares that all nuclear weapons are illegal. As a result of this discord, some NPT analysts see the coming NPT Review Conference as an inflection point that will shape the future of the global nonproliferation regime. Many countries will be looking for clear signals from the Biden administration on these issues, especially in terms of nuclear modernization, posture, and policy. Traditionally, NPT Review Conferences, which occur every five years, seek to create a consensus final document that outlines steps to strengthen all three pillars of the treaty. Due to the Covid-19 pandemic, the 2020 Review Conference has been rescheduled to be held no later than August 2021. As the Biden administration assumes office, ensuring the cohesion of the NPT and a successful Review Conference will require careful messaging about U.S. nuclear weapons modernization. The Biden administration should set a tone that it is willing to engage the international community in a cooperative and constructive manner and that it is willing to disagree respectfully.

Q6: What steps should the Biden administration take to ensure successful U.S. nuclear modernization?

A6: The nuclear arsenal is the bedrock of U.S. deterrence policy. Ensuring the safety, security, and reliability of the U.S. arsenal is an utmost national security policy priority. To advance these goals, U.S. policymakers should consider the following steps.

First, the Biden administration should ensure that modernization timelines are feasible and costs are realistic. Officials should create contingency plans to avoid national security lapses caused by programmatic delays. Many elements of the U.S. nuclear arsenal and infrastructure have aged well beyond their planned lifetimes. The United States cannot continue to kick the can on funding to secure near-term gains. The time to make hard decisions is now.

Second, the Biden administration should engage Congress and international partners in discussions of nuclear modernization. Maintaining an open ear to concerns will help create broader support for U.S. strategic objectives, including by assuring allies and engaging in credible arms control. There is room for middle ground, both in terms of our deterrence posture and arms control efforts that should complement rather than compete in support of strategic stability objectives. Finally, the Biden administration should ensure that any nuclear posture review is situated within broader DoD strategic objectives and conducted in a way that integrates across the spectrum of strategic challenges. U.S. nuclear policy and posture cannot operate in isolation. The rise of challenges posed by advanced conventional strike and hypersonic missile development, autonomous weapons, space, and cyber threats all present strategic threats that must be addressed in a comprehensive DoD strategy. In today’s complex and competitive security environment, the risk of crisis and conflict between nuclear-armed adversaries is on the rise. Improving conventional-nuclear integration and finding better ways to detect and manage escalation risks is critically important.

(Photo Credit: U.S. Air Force photo by Airman 1st Class Gerald R. Willis)