Bad Idea: Managing Government Like a Business

The vast majority of universities separate their business schools from their public policy schools. The lack of debate over this approach attests to the view that business is separate from policymaking. While core curriculums in business schools often include marketing, accounting, and corporate responsibility, public policy schools commonly require their students to study history, political theory, and the legislative process. Certainly, business and public policy are not mutually exclusive, but the qualifications of top leaders in both sectors fundamentally require a deep understanding of separate schools of thought. With this in mind, the recent political trend of approaching domestic and international policy as business deals to be won or lost can have negative implications for national security interests.

Transactions, negotiations, deals – whichever term one prefers – are made when two entities simultaneously benefit from an exchange. This exchange can be as simple as buying an apple from a market or as complicated as selling the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter to Japan. With respect to the former transaction, the customer eats a snack while the vendor adds to its daily revenue. The benefits of the latter transaction, however, are multifaceted and cannot be measured simply in dollars. For example, in addition to generating additional revenues (and jobs) for U.S. companies, sales of weapons such as the F-35 can contribute to Japan’s defense-industrial base development, allied war-fighting capabilities, greater interoperability with U.S. forces, and broader security and stability in the Asia-Pacific theater. Navigating the bureaucratic process for defense contracting, let alone the regulations and hurdles of the foreign military sales process, requires a deep understanding of and a career of experience with the monetary, historical, and political implications associated with such a ‘deal’ to make it successful.

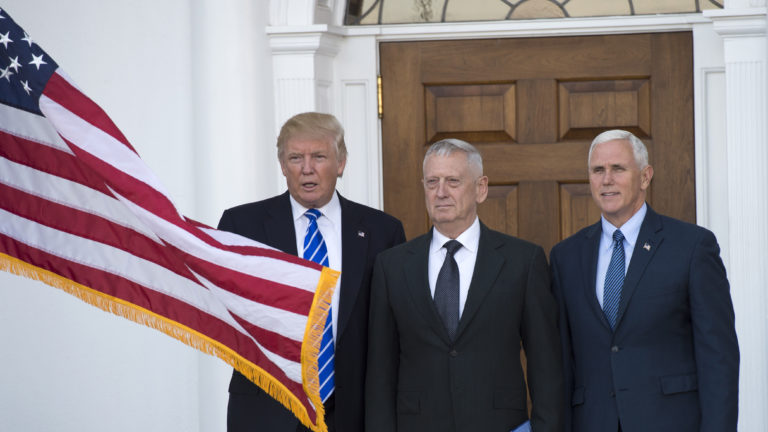

The strategy of ‘deal-making’ is a hallmark of the political approach employed by the Trump administration and some in Congress. But a deal-making approach is a simple-minded strategy for public policy that disregards crucial implications and complexities that are inherent in politics. Within the first year of the administration, a deal-making approach has been pursued in foreign policy and trade policy with negative ramifications for our national security.

Deal-making has dominated the President’s international communications and, in certain circumstances, has contradicted long-standing U.S. values, commitments to key allies, and military strategy. For example, during and after the President’s first diplomatic trip to Saudi Arabia, the Administration released statements highlighting the various “deals” made and emphasized significant foreign military sales (FMS). While FMS are generally good for the U.S. defense-industrial base, any agreement between the president and another foreign leader has much deeper implications than a mere contract.

For instance, the President verbally sided with Saudi Arabia in an embargo dispute with Qatar, seemingly unaware of or indifferent to the U.S. military’s sizable presence in Qatar. This presence includes both the forward headquarters of the U.S. Central Command, where more than 6,600 U.S. personnel are currently stationed, and substantial reliance on Al-Udeid Air Base for conducting operations throughout the Middle East. Inconsistencies with U.S. foreign policy such as this could be interpreted by U.S. allies as a reason to restructure or even revoke their partnerships with the United States, and there could be dire externalities if Qatar were to interpret these inconsistencies as grounds for expelling U.S. forces from its country. Approaching diplomatic missions as high-profile “deals” while not fully considering their broader impact on U.S. values and security interests could jeopardize key alliances, lead to instability in the region, and diminish the United States’ role as a world leader.

In terms of trade policy, the current Administration has pursued deal-making avenues that may appear harmless on the surface, yet overlook secondary implications that are important to national security. The Trump administration has tended to approach international trade as a zero-sum game where any gain by other countries is viewed as a loss for the United States. This policy view has crossed party lines with other political figures, including Senator Bernie Sanders (I-VT) and Senator Charles Schumer (D-NY), endorsing similar approaches during the last presidential campaign and in current policy debates on trade agreements.

While there are ways to ameliorate how the United States participates in international trade, brash or poorly reasoned decisions could lead to negative outcomes such as a trade war that adversely impacts the U.S. economy and national security. Proposed policies requiring U.S. corporations to re-locate their supply chains domestically would not only increase costs, but would also likely incentivize countries like China and Mexico to impose retaliatory trade restrictions. Protectionist restrictions could put at risk the United States’ ability to acquire raw materials, parts, and components that are uniquely developed abroad, such as specialized computer chips essential to many modern weapon systems. Likewise, protectionist restrictions could dissuade allies and partners from importing U.S.-made capabilities, which would negatively impact both the U.S. defense-industrial base and U.S. soft power abroad.

International trade is not a zero-sum game and there are a myriad of benefits and costs to consider in addition to the nominal amount of surplus or deficit. Trade deals can be and often are win-win because they can generate economic growth and strengthen security in all countries that are part of the deal. While international trade has positively contributed to the efficiency of global production and consumption and has raised the standard of living for billions of people around the world, international trade can also be used as a political tool to enhance national security. For example, international trade has been used to dissuade countries from practicing anti-democratic values through the imposition of economic sanctions or embargos. Additionally, international trade has been used to integrate countries economically to avoid future military conflicts, such as the European Union. The national security benefits of trade deals should not be overlooked and are often equally or more important than the economic benefits.

The U.S. withdrawal from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) diminishes the United States’ soft power abilities in the Asia-Pacific theater. In a time of rapidly emerging markets coupled with volatile security threats in the region, the United States has much at stake in maintaining its leadership role in the region. TPP created pathways for the United States to navigate and participate in rapidly emerging Asian markets that could one day pose a threat to U.S. industry. TPP would have strengthened U.S. partnerships with Asian allies that could benefit U.S. security interests and military presence in the region. Asian markets will continue to grow whether the United States participates or not. Thus, it is in the interest of the United States to be engaged economically and politically in the region and acknowledge that American security interests lie both domestically and abroad.

While there is always room to improve U.S. policy, approaching policymaking with a business-oriented, deal-making focus can be counterproductive to maintaining American national security. Policy makers must be mindful of the many non-monetary factors that are part of both international and domestic policy. While economic interests at home and abroad are certainly important, they must be balanced with broader national security interests. The current administration’s trend towards deal-making in public policy is reversing decades of hard work from established, experienced policymakers and statesmen, and if continued, could permanently damage U.S. interests abroad. Filling many of the still vacant administration positions with experienced, career-policymakers could balance out the currently business-dominated qualifications of top officials moving forward.

This report is produced by the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), a private, tax-exempt institution focusing on international public policy issues. Its research is nonpartisan and nonproprietary. CSIS does not take specific policy positions. Accordingly, all views, positions, and conclusions expressed in this publication should be understood to be solely those of the author(s).

© 2017 by the Center for Strategic and International Studies. All rights reserved.

(Photo courtesy of DON EMMERT/AFP/Getty Images)