Bad Idea: Innovation Theater

Bad Ideas in National Security Series

The Department of Defense (DoD) has made a deliberate effort in recent years to improve the speed of innovation in defense. These efforts, perhaps unsurprisingly, have resulted in a number of new initiatives and an alphabet soup of organizations intended to improve innovation—DIU, SCO, AFWERX, SOFWERX, NSIC, and the recently created OSC (Office of Strategic Capital) to name just a few of the more than 20 organizations that have been created so far. Each new initiative and organization is announced with optimism and enthusiasm, and the motivation behind each appears to be genuine. But these efforts have resulted in what some have labeled “innovation theater” rather than real innovation due to a lack of follow-through and “benign neglect” from top defense leaders. Continuing down this path of innovation theater is a bad idea because it does little to advance the hard but necessary work of changing how the defense enterprise operates and its willingness to adopt innovative ideas and technologies.

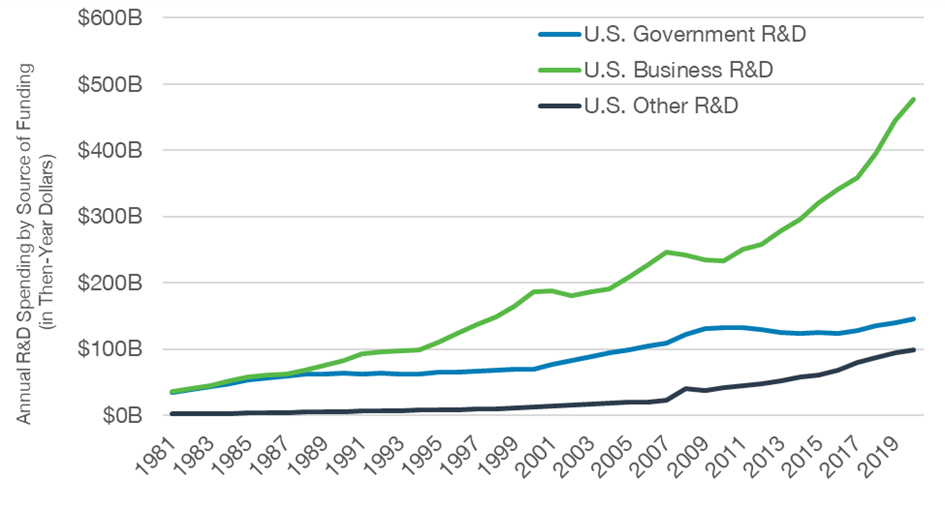

At the root of the issue are two simple truths. First, the center of innovation in many areas is no longer the U.S. government or the Defense Department. And second, that shift is not a problem to be rectified but rather an opportunity to be exploited. As shown in Figure 1, U.S. private-sector (business) funding for all research and development began to exceed U.S. government funding in the 1980s, and the gap has only accelerated since then. But the takeaway is not that DoD and the U.S. government overall need to spend more on R&D to catch up—that is a fool’s errand. DoD’s budget for research, development, test, and evaluation (RDT&E) is already at a historic peak in both inflation-adjusted dollars and as a percentage of the DoD budget. Rather, the takeaway from Figure 1 should be the potential strategic advantage that the massive growth in privately funded R&D represents over our adversaries—if DoD can learn to fully embrace and leverage commercially developed dual-use technologies. It effectively serves as a budget multiplier in an era where the value of defense dollars is being eroded by higher labor costs and higher operating costs.

Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, Gross domestic spending on R&D

Many of DoD’s innovation initiatives are rightly focused on leveraging commercial or dual-use technologies, but they are often overly concerned with solving problems rather than taking advantage of opportunities. To reorient, the U.S. defense enterprise needs to clearly define the opportunity: commercially-driven innovation can be a source of enduring and asymmetric advantage over China and Russia. The advantage is asymmetric because the U.S. private sector is widely considered more vibrant and innovative than that of U.S. competitors. The culture of entrepreneurship in the U.S. private sector encourages risk-taking and innovation, and it thrives on a well-educated workforce and a highly developed venture capital and private equity industry that funds commercial investments in innovation. This asymmetry is also evident in the fact that our adversaries are constantly trying to steal technology from our companies. More importantly, commercially driven innovation is an enduring advantage because is rooted in our open society and free market economic system—something our adversaries are loathe to replicate because it would erode the foundation upon which their authoritarian regimes are built.

To be clear, commercial technology is not the answer to all of DoD’s innovation challenges—it is only one area of the overall competition, but one in which we have a distinct advantage. There are many other areas of military competition in which commercially funded innovation is not sufficient. Highly specialized military missions and platforms, such as nuclear weapons, aircraft carriers, and stealthy aircraft, will largely continue to require a traditional government-funded and directed investment model. And many types of basic and applied research are too risky—and their applications too uncertain—to make sense for private sector investment. If the government does not pay for R&D in these areas, it is not likely to happen. But there is increasing overlap between the capabilities needed to support many military missions and the capabilities being developed and matured through private investments—in space, cyber security, cloud computing, artificial intelligence, and other areas. The overlap between the technologies in which the private sector is already investing and the capabilities needed by the military defines the opportunity space in which DoD’s innovation initiatives should focus.

Instead of continuing to engage in the theater of announcing new organizations and new initiatives backed by paltry funding, DoD needs to do two things: (1) follow through with what it has already started and (2) pivot its efforts to focus on leveraging rather than leading.

The key to following through on existing initiatives is fundamentally about funding and authorities. It may seem counterintuitive, but initiatives to leverage privately funded commercial innovation require some DoD funding. But this funding needs to be flexible, which may require funding mechanisms, such as working capital funds, that give DoD the tools it needs to work more effectively with industry and be a good customer. DoD also needs to plan and program for the long-term funding real innovation requires. Five-year funding projections demonstrate commitment on the part of the government, which can incentivize private capital investments by giving companies greater insight into the potential defense market for dual-use technologies. In addition to funding, leveraging commercial innovation may require new or expanded authorities from Congress or rethinking how existing authorities are applied.

DoD also needs to focus on leveraging rather than leading. The military as an institution is habituated to leading R&D efforts, and this role made sense in the post-World War II era when government investments in R&D (and defense R&D in particular) were the predominant source of funding for innovative technology. That is no longer the case, and DoD should not view commercial innovation as something it can dominate or direct. DoD’s most effective role is as a good customer and matchmaker rather than as an investor or director. It should not attempt to direct how private sector investments are applied and should have a light touch in setting requirements because it often does not have the expertise, authority, or stomach for what this requires. Innovation is messy, disruptive, and frequently involves repeated failures. Intervening in commercial markets can be self-defeating for defense because it undermines the very foundation of what makes commercial innovation an enduring strategic advantage for the United States: the “invisible hand” that continually directs and redirects the allocation of capital. Instead, DoD should use an effects-based acquisition approach (as opposed to a requirements-based approach) that opens more opportunities to innovative solutions, whether they are from commercial firms or more traditional defense companies. This puts DoD in its most effective role as a customer that is looking to buy innovative solutions rather than as a designer/investor looking to direct innovation.

DoD rightly understands the need to harness commercial innovation for defense, as the many organizations and initiatives it has created over the past decade demonstrate. The opportunities to create enduring asymmetric advantages across many areas of the military and economic competition are simply too great to ignore. But without funding, authorities, and a focus on leveraging rather than leading, these efforts will amount to little more than theater.

(Photo credit: DVIDS/Air Force Research Laboratory. The appearance of U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) visual information does not imply or constitute DoD endorsement.)