Bad Idea: The Misguided Quest to Recreate USIA

Recreating the United States Information Agency (USIA) is a bad idea that just won’t die. Its lasting appeal tells us something important: nearly two decades after 9/11, the United States is still grappling with how best to design and execute a government-wide global information and engagement strategy, counter disinformation and propaganda, respond to the weaponization of social media, build long-term relationships with key opinion leaders, and proactively shape public opinion to advance U.S. foreign policy objectives. Some call this collection of issues “public diplomacy.”[1] A 2010 CNAS report I co-authored with Marc Lynch adopts the term “strategic public engagement.” Regardless of the moniker, the need to address these challenges systematically and at scale is critical. Fortunately, there are better solutions available than recreating USIA. And most build on organizational structures, capabilities, activities, and personnel that are already in place.

USIA was a formidable asset to the United States as it fought the elements of the Cold War relating to the contest over ideas, ideology, and public opinion worldwide. It was shuttered and merged into the State Department in 1999 as part of a multi-prong deal with then-Senator Jesse Helms. USIA nostalgia emerged quickly in the aftermath of 9/11, when it became abundantly clear that no individual agency owned or was properly equipped for what was (unhelpfully) dubbed the “war of ideas.” The nostalgia continues to this day.

Re-creating USIA is the wrong solution to a real set of problems. Here’s why:

First, USIA had the benefit of organizing mainly around the single, if complex, ideological threat of fighting communism. Today’s challenges are more diffuse. They include but are not limited to countering geopolitical threats from China, Russia, and the appeal of authoritarian models of governance; countering violent extremist ideologies; effectively engaging the largest population of youth in human history; countering harmful disinformation on everything from the safety of a COVID-19 vaccine to refugees and minority groups to the causes of climate change; building public support in allied countries for sustained partnership with the United States; and proactively bolstering an image of the United States as a hub for innovation, education, and research — all keys to U.S. competitiveness globally. It is hard to imagine any one agency that could effectively work across all these issue areas, let alone work constructively with other agencies in all of these domains.

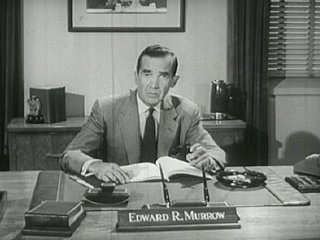

Second, communications and policy-making move exponentially faster than they did during the Cold War. There was more time to consult across agencies, coordinate, and respond to global events. Now events turn on a dime, or a tweet. Creating a new government bureaucracy seems an odd way to create the agility and focus that is now needed in our government. Furthermore, USIA nostalgia glosses over the reality that USIA too found itself sidelined on occasion, leaving even its storied director Edward R. Murrow to lament that his agency be brought “in on the take-offs not just the crash-landings.” To be most effective, strategic information and public engagement activities must be deeply and continuously embedded across a full range of policies and their execution. They must be systematically deployed as a force multiplier in concert with other instruments of power.

Third, in USIA’s time, the distinctions between diplomacy and public diplomacy, politics, and governance, were once clearer. News was more filtered and some topics were considered off-limits. More discussions and activities could occur outside of public scrutiny or partisan politics. Communications and public engagement could be more easily separated from the day-to-day work of diplomats and government officials. For good or ill, they are now inseparable. No senior official would or should give up this part of their portfolio. They would be hamstrung if they did.

Fourth, when it comes to strategic information and public engagement activities, one of the most severe challenges our government confronts is coping with overlapping roles and responsibilities, competition, and lack of coordination across agencies. Adding yet another government bureaucracy to this mix seems akin to joining twenty new social media platforms to solve the problem of information overload.

Fifth and finally, the main reason people advocate for recreating USIA is to achieve impact at a far greater scale — but that can be done with existing structures and larger budget.

A Better Alternative

It is not useful to simply critique USIA nostalgia, however. So, what would a better way look like?

To start, the National Security Council (NSC) should develop U.S.-government (USG)-wide strategies and coordinate all USG information and strategic public engagement activities. A deputy national security advisor should direct a small internal unit of the NSC and chair an interagency coordinating process with senior representatives from all relevant agencies. The NSC should avoid becoming operational.

The State Department should then take the lead in executing all overt information and strategic public engagement activities with the U.S. Agency for Global Media (USAGM), which should take the lead in all U.S. international broadcasting. The State Department should also significantly expand the capabilities of the Global Engagement Center (GEC), which develops targeted strategies, programs, research, and analysis to support the USG’s work to counter disinformation and propaganda. It should consider creating GEC hubs based in major world regions. In general, strategic public engagement and information activities must be properly resourced, staffed, and supported by analysis and intelligence. They need to be staffed by professionals who possess the distinctive set of skills and knowledge required and directed by people with a proven ability to lead. Persistent misalignment of resources and objectives remains the single most important obstacle to success.

Across different government agencies, evaluation must be radically improved. Though it is not easy to measure success, it is possible. The USG should invest in developing shared metrics, collecting and analyzing structured data, measuring results, and iterating programming to enhance impact. The USG should also work more closely to align strategic public engagement and anti-disinformation activities with allied countries and other partners around the world.[2] This can be done both bilaterally and multilaterally. Another key effort should be to reach out to the private sector to create consistent and ongoing strategy and processes to partner with social media companies and also to build “an information ecosystem that works in the interests of democracies.” Finally, the USG should develop a new strategy for broadcasting overseas, led by USAGM. It should develop separately a new evidence-based strategy to support independent media around the world, recognizing geopolitical competition and insecure business models.

There are also ways to promote non-government exchange. For example, new exchange and leadership programs should focus on advancing priority policy objectives. A new administration could create a network of global leaders advancing climate change, accelerating green economic growth, or fighting corruption. The USG could develop for other world regions an equivalent to the highly successful Young African Leaders Initiative. It could develop a strategy to engage the global youth population — now the largest in human history and concentrated in critical countries and regions — that will shape the future. Additionally, alumni networks could be leveraged more strategically and more holistically, and engaged to advance larger policy and information initiatives as appropriate.

Overall, the USG still needs more effective and systematic engagement with private and non-profit organizations to amplify the effects of USG strategies. Some of this can be done within existing USG structures through partnerships, grantmaking, and procured services. Other valuable activities may be harder or even impossible to accomplish within government. Outside groups have the potential to leverage their own distinctive credibility and voice with target audiences, act more nimbly, engage audiences that official U.S. actors cannot, and take greater risks. They can leverage private dollars while avoiding the impression of “pay for access” bargains that public officials can unintentionally create when they raise private funds for worthy causes. These goals and others could be accomplished by establishing a new independent entity or by leveraging existing organizations such as the National Endowment for Democracy and United States Institute of Peace. The function could also be subcontracted to existing nonprofits, universities, and research organizations with a proven ability to deliver results and engage diverse networks.

The goal of all of these activities is to advance U.S. foreign policy and national security objectives by engaging foreign publics through information, education, exchange, and engagement activities. These functions must be expanded and integrated throughout USG agencies, must be more strategic and data-driven. They should not be the role of yet another new government bureaucracy.

This approach also recognizes how much has changed over the last twenty years. U.S. public diplomacy, and everything behind it, is far from perfect. But it has changed substantially, becoming more integrated and more connected to foreign policy. The challenge now is to sufficiently staff, equip, and scale it in ways that reflects the new realities of global information competition. Recreating USIA would detract from that goal, not add.

CSIS does not take specific policy positions; accordingly, all views expressed above should be understood to be solely those of the author.

[1] The report defines strategic public engagement as defined as” the promotion of national interests through governmental efforts to inform, engage, and influence foreign populations. [2] See Nina Jankowicz & Henry Collis, “Enduring Information Vigilance: Government after COVID-9,” Parameters 50, no. 3 (2020), https://press.armywarcollege.edu/parameters/vol50/iss3/4