Bad Idea: Cutting the Military Housing Allowance

Like a zombie in a low-budget horror film, a bad idea that keeps coming back to life is the proposal to scale back the military housing allowance. In last year’s National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA), the Senate version of the bill included a provision that would have limited the housing allowance to only what service members actually spend on housing rather than providing a flat rate based on rank, location, and number of dependents as is currently the case. While this change didn’t make it into the final bill last year, the Senate Armed Services Committee (SASC) took another shot at the housing allowance in this year’s NDAA. This year’s proposal would have prevented dual-military married couples from receiving the extra housing allowance for dependents. But again, this change was removed in conference committee.

As someone who has argued for compensation reform in the past, I sympathize with SASC’s attempts to reduce compensation costs. And the proposed changes sound perfectly reasonable on the surface. Under the current housing allowance rules, if service members find housing that costs less than the allowance, they get to keep the difference. And if two service members are married and living together, they get both of their housing allowances. The change the Senate proposed last year would have limited the housing allowance to only what service members actually spend. Seems fair, right?

But if one stops to think through this idea, several problems emerge. The most obvious problem is the behavior this change would incentivize. Consider a first lieutenant (an O-2) with no dependents stationed at the Pentagon. She currently receives a housing allowance of $2241 per month, but if she gets an apartment with roommates, her share of the rent may be substantially less than that. With this change, she would no longer get to keep the difference. So what incentive would she have to economize and live with roommates? She would instead be incentivized to use the full amount of the housing allowance and get her own place or move with her roommates to a larger, more luxurious apartment with better amenities—limiting or negating the savings to DoD. The housing allowance would effectively become a use it or lose it benefit.

Proposals to reform the military housing allowance often fail to recognize that, despite its name, it is not really about housing at all. When the FY 1998 NDAA combined the Basic Allowance for Quarters and the Variable Housing Allowance to create the Basic Allowance for Housing, it fundamentally changed the benefit. From a service member’s perspective, the allowance transformed from a reimbursement for housing costs to a new form of cash compensation. And it is a particularly attractive form of cash because it is not subject to federal taxes. It is also an attractive way for Congress to increase cash compensation for the military because it doesn’t incur additional liability for retirement pensions, since retirement pay is based on a member’s basic pay not including allowances.

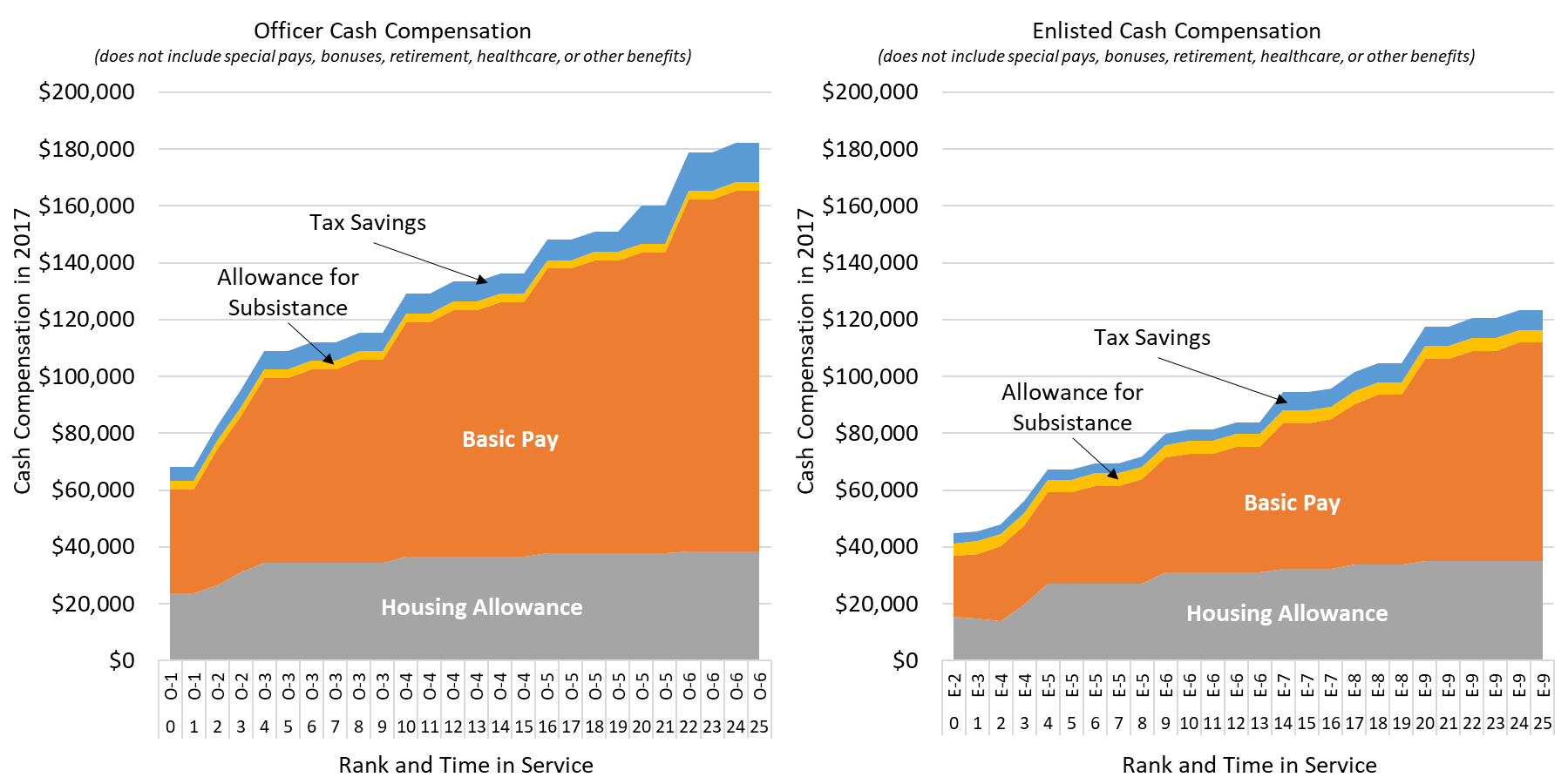

For junior officers and enlisted of all ranks, the housing allowance is about one-third or more of total cash compensation, as shown in the figure below. Changes in the housing allowance like the Senate has proposed would mean a significant reduction in overall cash compensation, particularly for lower-ranking service members. For example, the provision in this year’s Senate version of the NDAA would have prevented dual-military married couples from receiving the higher housing allowance for dependents if they are stationed together. For two married E-5s this would mean a reduction of $5,200 in annual cash compensation each, including lost tax savings, or $10,400 in total. Eliminating the housing allowance entirely for one partner would be a cut of more than $30,000 in annual cash compensation for the family. Worse yet, it could actually discourage couples from getting married in the first place to avoid the financial penalty.

The proposal from last year to reimburse only the actual out-of-pocket housing costs would also be a major cut in cash compensation, although the amount of the reduction would vary based on how much people currently spend on housing. This change could also affect the local housing market around major military installations. When service members are incentivized to spend the full amount of their housing allowance (or else lose it), landlords could also be incentivized to jack up rents to take advantage of the higher spending incentives provided to service members. This could completely distort the local housing market, driving up prices and making housing less affordable for low- and middle-income civilian families who live near a military base.

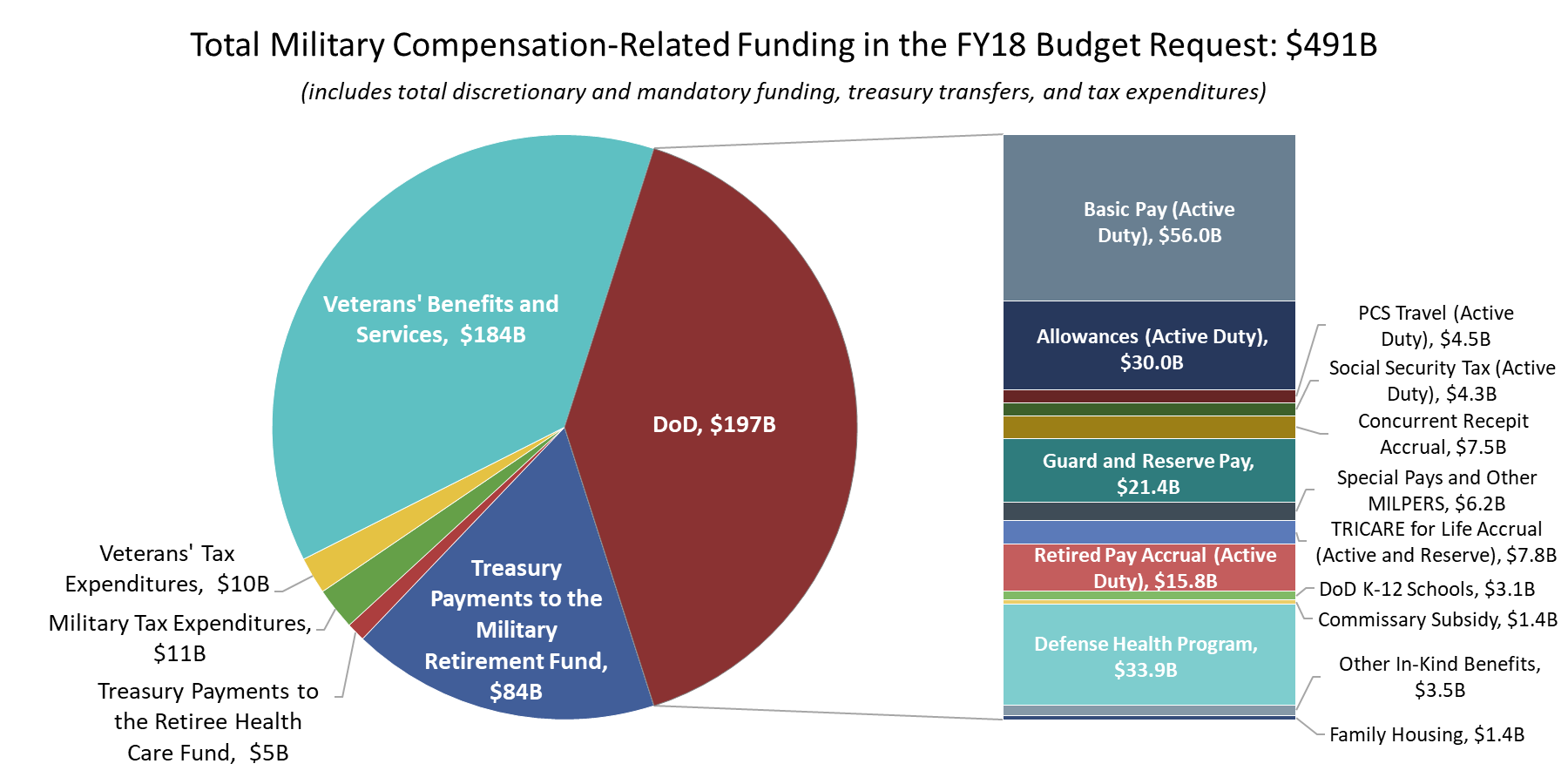

While I fully understand the Senate’s desire to cut back on excessive benefits, this is not a wise way to do it. Immediate cash compensation is what employees value most—more than non-cash forms of compensation (like healthcare) and deferred benefits (like retirement pensions). That’s why private sector employers spend about 70 percent of total compensation costs on cash compensation. For DoD, cash compensation is less than half of total compensation costs. And if veterans’ benefits like the GI Bill and other benefits funded outside of the defense budget are included, the fraction of cash compensation for the military is even lower, as shown in the figure below. In the FY 2018 budget request, cash compensation for the military is just $125 billion out of some $491 billion in military compensation-related costs across the federal budget.

Non-cash and deferred benefits divert resources from other priorities in the budget, such as funding for readiness, growing the force, and modernizing weapon systems. Moreover, the excessive reliance on non-cash and deferred benefits makes the military’s compensation package more expensive and less competitive with private sector compensation plans. This is part of the reason the Air Force is having so much trouble retaining pilots.

If Congress wants to control costs, it should focus on cutting the forms of compensation that are less valued by service members and leave cash compensation—like the housing allowance—alone. Tremendous savings can be achieved by tweaking benefits many service members don’t even know they have and therefore do not value commensurate with their costs, like the Medicare Eligible Retiree Healthcare benefit (a.k.a. TRICARE for Life). Of course, compensation is just one of many factors at play when people decide to join and stay in the military, but it is one of the main ways policymakers can influence those decisions. It is a key tool in DoD’s ability to attract and retain the highly skilled and high-performing personnel it needs. The war for talent is a war the military can’t afford to lose.

This report is produced by the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), a private, tax-exempt institution focusing on international public policy issues. Its research is nonpartisan and nonproprietary. CSIS does not take specific policy positions. Accordingly, all views, positions, and conclusions expressed in this publication should be understood to be solely those of the author(s).

© 2017 by the Center for Strategic and International Studies. All rights reserved.

(Photo courtesy of U.S. Army flickr, U.S. Marine Corps photo by Cpl. Amaia Unanue)