Bad Idea: The Officer-Enlisted Divide

Introduction

Personnel in the U.S. military are divided into two tiers: commissioned officers and enlisted service members.[1] Officers are commissioned by the President of the United States and sworn to support and defend the U.S. Constitution. Enlisted members additionally swear to “obey the orders of the President of the United States and the orders of the officers appointed over” them.[2] Chief Master Sergeant of the Air Force JoAnne Bass, the highest-ranking enlisted member in the Air Force with nearly 30 years of experience in the military, is obligated by military customs and courtesies to salute the newest second lieutenant right out of Officer Training School (OTS). In support of maintaining the current system are four commonly cited arguments: tradition, enlisted not seeking the “burden of command,” senior enlisted acting as subject-matter experts to officers, and issues of career longevity. In this article, I will examine each of these arguments and propose an alternative structure that meets today’s needs.

Shortcomings of the Current System

The two-tiered system is based on antiquated and classist British military tradition that stymies the effectiveness of today’s armed services.[3] Merging officers and enlisted personnel into one hierarchical pyramid will unleash untapped leadership potential, remove redundancies, and put people in the positions for which they are best suited.

Tradition

“That’s how we’ve always done things” is perhaps the laziest reason to continue anything, yet it is a principle lauded by the military. Modern problems require modern thinking, and we should not be held back by a sclerotic organizational structure unable to adapt to today’s demands. Military officers, who have spent their career reaping the benefits of the two-tiered system, often see little need for change. However, they are the only ones able to advocate change to Congress — enlisted members lack both clout and the voice to appeal for needed radical change. Furthermore, some argue that given the cooperation with allied forces, altering our current rank system would disrupt interoperability. Although there will be an adjustment period, the U.S. military adopted the rank structure of the most dominant military force of the time, and so too will other countries if the U.S. military changes its rank structure.

“The Burden of Command”

This argument stems from the idea that most enlisted service members either do not want or are incapable of commanding. Those with the interest or capability simply need a Bachelor’s degree, a few months to attend OTS/OCS, and their command’s approval to become “Mustangs,” a nickname for prior enlisted officers. This misses the point and underplays the difficulties inherent in uprooting your career and family to pursue advancement. Enlisted leaders still lead without exercising technical “command” because of their interpersonal and professional skills honed after a long career. They are often referred to as “the backbone of the military,” without which the military would collapse. This positional authority carries with it a significant burden that goes unrecognized by the current order. Certainly, there are enlisted members without any desire for command, who are happy doing their work and going home; but this logic applies to officers as well. Additionally, some officers say that it is lonely at the top, and those who would rather “stay with the troops” would do better as enlisted service members. In reality, enlisted service members are often moved around and forced to adapt to changing units on a very regular basis. In a one-tiered system, leadership positions could be, for example, special opportunities that would be sought out by those most able and willing rather than allotted to a higher military class.

Subject-Matter Advisors

Still, others argue that the two-tiered system ensures that new and seasoned officers can rely on senior enlisted members as masters of their trade. Officers and enlisted having such different careers facilitates a diversity of thought that would otherwise be impossible. Diversity is an important step in avoiding groupthink, but it can be achieved without maintaining a two-tiered system. Experienced military members of all backgrounds should be willing to mentor and seek counsel from subordinates, peers, and supervisors. Conventional thinking is that officers are groomed to be generalists, while senior enlisted are made to be technical experts in their fields. However, senior enlisted members can also have tremendous leadership capabilities and generalist knowledge because they understand how the parts need to work together. This is the gap that warrant officers fill in certain branches of the military. By maintaining the two-tiered system, we are depriving the Department of Defense (DOD) of potential leaders who have both subject-matter expertise and the leadership experience necessary for success.

Longevity

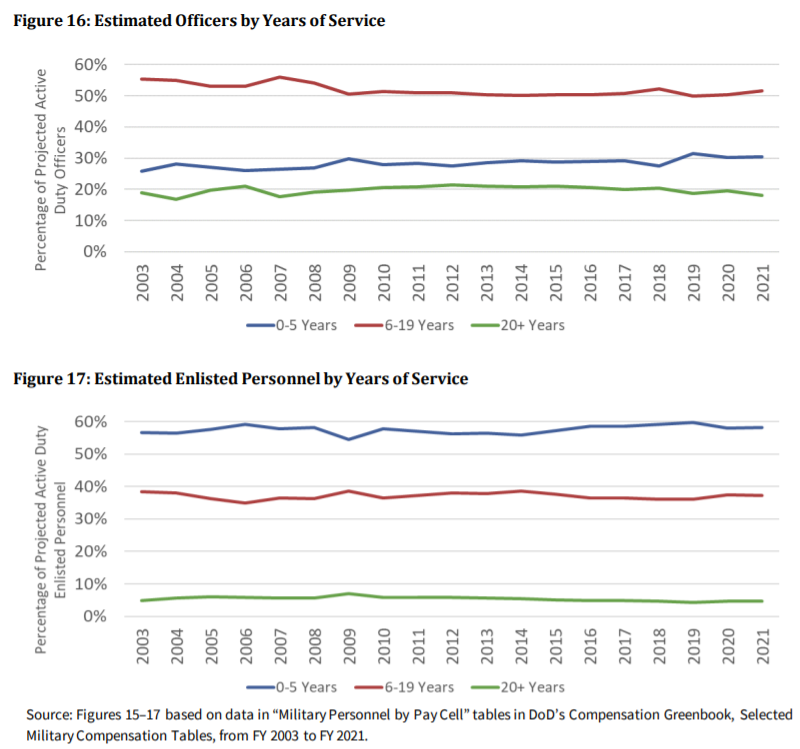

The last oft-cited argument is the fact that enlisted members are prone to leaving the service after their first tour, whereas officers frequently provide a much-needed sense of continuity and experience by remaining in their careers for 20 years or more.

I do not argue the statistics: the figures above show that almost 60% of enlisted members will serve five years or less. Service members serving over 20 years are more than twice as likely to be officers than enlisted. However, citing this as a reason to maintain the divide treats enlisted members as expendable and to some extent, less committed to the mission. Enlisted members are subjected to worse living conditions, worse pay, and fewer educational opportunities than their commissioned counterparts, so it should be no surprise that retention is lower. Additionally, these statistics do not discriminate between voluntary separation to pursue better opportunities, being evaluated as medically unfit due to service-related issues, and being forced out due to turnover. Consolidating the force would ensure greater opportunities for all service members and incentivize more of them to stay longer.

Moving Forward

The most recent National Defense Strategy states that “Cultivating a lethal, agile force requires more than just new technologies and posture changes; it depends on the ability of our warfighters and the Department workforce to integrate new capabilities, adapt warfighting approaches, and change business practices to achieve mission success.” Fulfilling the mission calls for a radical restructuring of the military’s defunct organizational structure which, given institutional pushback, many leaders may scoff at. Fortunately, there is already a one-tiered rank system the government uses to delineate experience effectively: the Department of State’s Foreign Service ranks. In this system, there is a numbered ladder system with one being the highest and nine being the lowest, with 14 pay steps for each. Additionally, the Senior Foreign Service comprises the top four ranks, equivalent to the general and flag ranks of the military. Foreign Service Officers generally enter between ranks four to six depending on experience and background. This hierarchical system entrusts its officers with increasing responsibility, from tactical to strategic levels, with no delineation of a superior class or permanent limitations imposed based on the educational level attained at the time the person first enters service.

What is needed for a modern force is a redesigned rank system that holistically assesses education as well as private and public sector work experience. New military members would receive appropriate ranks and training, and they would promote as quickly or as slowly as their work and abilities dictate. Ending the institutional divide will give the military the necessary dynamism to attract, retain, and profit from the leadership and experience of a greater number of candidates. As the military’s newest branch, the Space Force has the greatest opportunity to eschew organizational momentum and take risks for rapid evolution. Rather than continuing an archaic tradition, the Space Force could be the first branch to lead the way towards a more equal and efficient military.

[1] There are also warrant officers in the U.S. Marine Corps, Navy, Army, and Coast Guard who are organizationally subordinate to commissioned officers and superordinate to enlisted service members.

[3] The origin of the officer system in Britain stemmed from the purchase system, ensuring that officers were of “good family” and had access to money not specifically through the king to ensure political affiliation to the Whigs. https://www.worldcat.org/title/purchase-system-in-the-british-army-1660-1871/oclc/7308080.

The views expressed are those of the author and do not reflect the official position of the U.S. Air Force or Department of Defense.

(Photo Credit: Petty Officer 1st Class Jonathan Pankau. The appearance of U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) visual information does not imply or constitute DoD endorsement.)