Bad Idea: Moving OCO Back into the Base Budget (While Negotiating a Budget Deal)

Of the numerous and often recurring debates on U.S. defense spending, one that has attracted particular attention over the past several years is the use of the Overseas Contingency Operations (OCO) budget. The OCO budget is designated to fund war-related activities and consequently, is not subject to the budget caps imposed by the Budget Control Act of 2011 (BCA). As a result of this exemption from the spending limits, however, OCO has been taken advantage of to skirt the budget caps on defense spending and to fund base budget activities that do not actually constitute war funding.[1] The use of OCO funding for base budget activities was one of the worst-kept national security secrets until the FY 2016 budget request when the Department of Defense (DoD) announced it would “propose a plan to transition all enduring costs currently funded in the OCO budget to the base budget beginning in 2017 and ending by 2020.” At the time, DoD “tacitly acknowledged” that $30 billion of the $50.9 billion OCO budget covered enduring costs; an October 2019 report from the Congressional Budget Office approximated that nearly 70 percent of the FY 2019 OCO request for $69 billion is used to fund base budget activities.

The use of OCO to fund base budget priorities poses significant transparency concerns over the cost of wars in Afghanistan, Iraq, and Syria. This practice earned the ire of members of Congress on both sides of the aisle, particularly then-representative Mick Mulvaney who referred to the war funding account as a “slush fund.” It should come as little surprise then that the Pentagon, under a Trump administration with Mulvaney at the helm of the Office of Management and Budget, included plans to pull enduring costs in OCO back into the base budget in its FY 2019 budget request. Returning OCO to the base budget is a positive move that increases transparency and accountability within the Pentagon and is a policy endorsed in the report of the National Defense Strategy Commission. However, returning enduring OCO costs to the base budget, particularly a vast majority of those enduring costs over a short period as DoD has outlined, could significantly complicate an agreement between congressional Democrats and Republicans to increase both the defense and nondefense BCA budget caps for FY 2020 and FY 2021.

With the impending expiration of the two-year Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018 (BBA 2018), Congress must reach an agreement to increase the budget caps for the next two fiscal years, FY 2020 and FY 2021. As shown in Table 1, the BCA spending limits for the base defense budget are set at $576 billion and $590 billion, respectively, for the next two years. The administration originally projected a total national defense budget of $733 billion for FY 2020 and $742.8 billion for FY 2021. Included within those toplines are OCO budgets, exempt from the spending caps, of $73 billion and $65.8 billion, respectively.

Table 1. FY 2020 – FY 2021 BCA Budget Cap Adjustments to Meet FYDP Projections (discretionary budget authority in current dollars)

| FY 2020 | FY 2021 | |

| Projected Total National Defense Spending Levels (050) | $733B | $742.8B |

| Projected OCO Level* | $73B | $65.8B |

| Projected Base Budget (050) | $660B | $677B |

| Current BCA Budget Cap | $576B | $590B |

| Difference: | $84B | $87B |

*From OMB budget authority projections

As depicted in the table above, the defense spending caps would have to be raised by $171 billion in total for the two-year period to support the projections outlined by the administration. President Trump’s recent announcement of a national defense topline of $700 billion for FY 2020—a 4.5 percent cut from the projected level for the next fiscal year—would necessitate a smaller increase in the budget cap, approximately $55 billion depending on the OCO level designated under that topline.

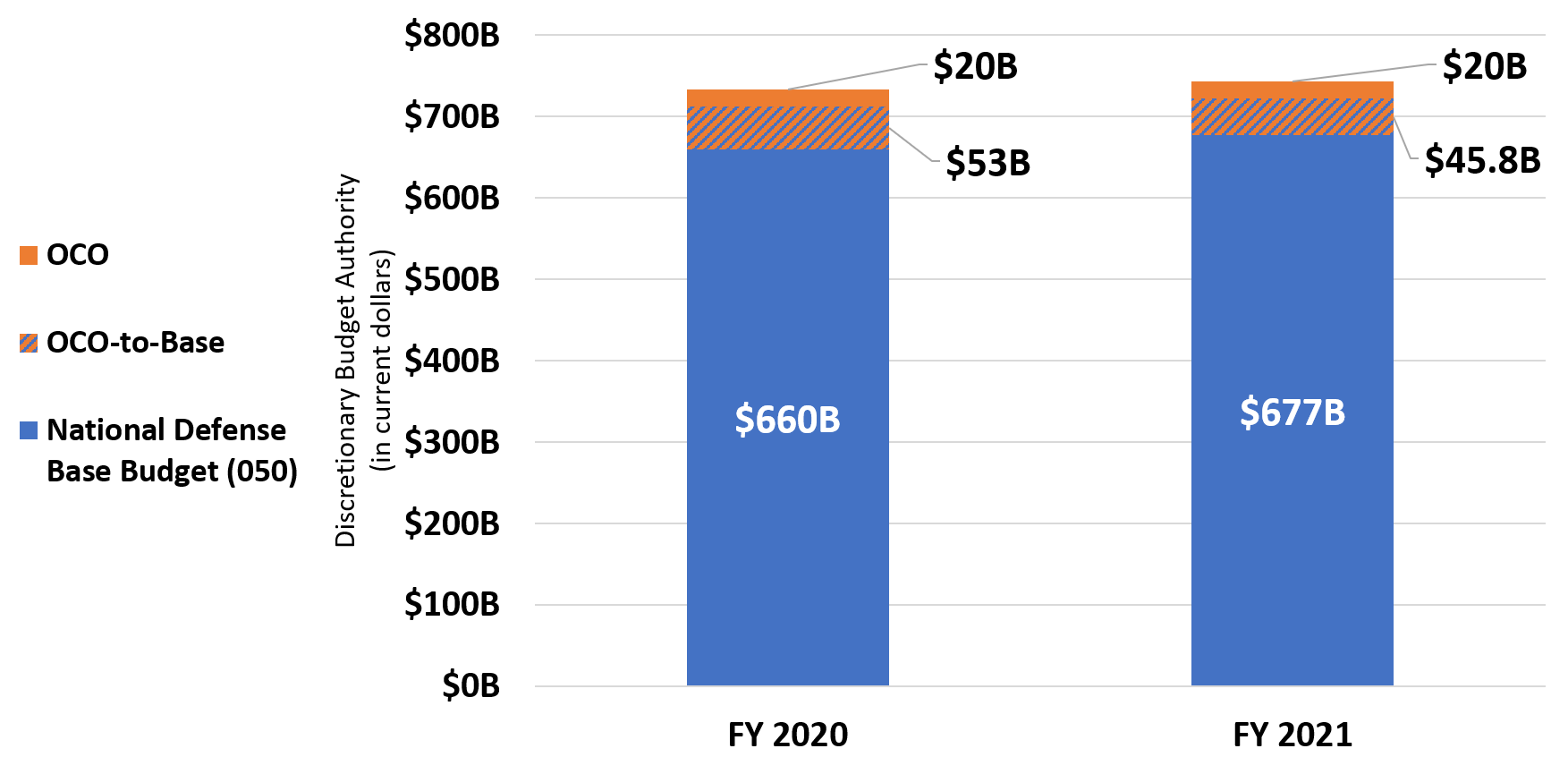

However, if DoD decides to follow through on its plan to shift enduring costs from OCO to the base budget, the budget cap landscape changes dramatically. In its FY 2019 request, DoD projected OCO levels of $20 billion for FY 2020 and FY 2021 each. As shown in Figure 1, this means that the Department would transition $53 billion from OCO into the base budget for FY 2020 and $45.8 billion for the next fiscal year.

Figure 1. Projected FY 2020 – FY 2021 National Defense Budget Authority

Shifting these enduring costs into the base budget would require greater increases in the defense spending caps to support the administration’s projections for national defense spending. As Table 2 illustrates, the caps would need to be raised by a total of approximately $270 billion dollars for the two-year period.

Table 2. FY 2020 – FY 2021 BCA Budget Cap Adjustments to Meet FYDP Projections and DoD OCO-to-Base Transfer (discretionary budget authority in current dollars)

| FY 2020 | FY 2021 | |

| Projected Total National Defense Spending Levels (050) | $733B | $742.8B |

| Projected OCO Level | $73B | $65.8B |

| OCO-to-Base Transfer | $53B | $45.8B |

| Projected Base Budget (050) | $713B | $722.8B |

| Current BCA Budget Cap | $576B | $590B |

| Difference: | $137B | $132.8B |

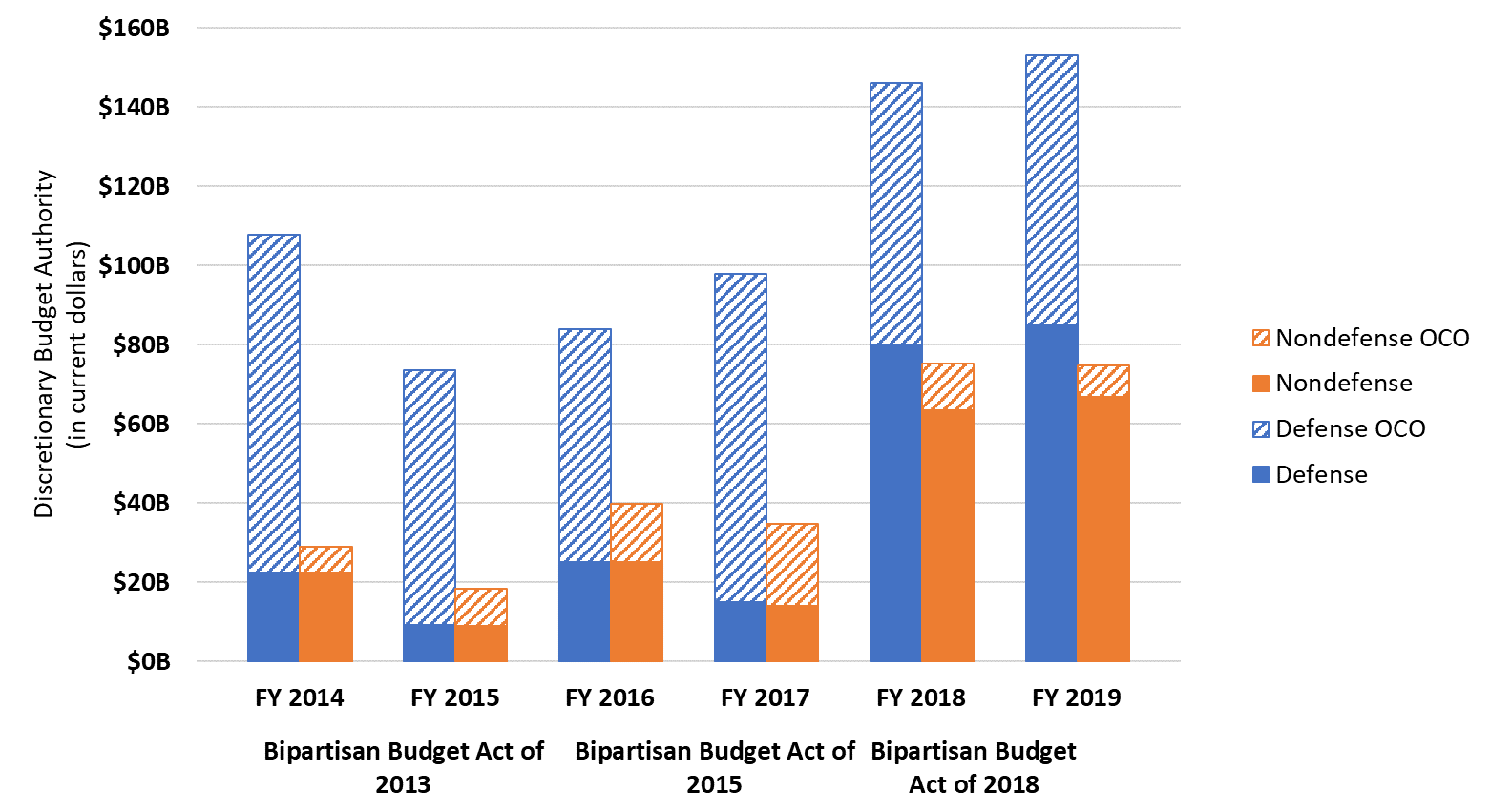

How does this scenario compare to defense cap increases in previous budget deals? Figure 2 depicts the spending cap increases for both defense and nondefense over the past three budget agreements. The $270 billion increase in the defense budget caps required to meet the projected FY 2020 and FY 2021 funding levels while returning enduring costs into the base budget would be larger than the defense increases in all of the previous budget deals combined. More significantly, however, the Democrats’ capture of the House in the 2018 midterm elections most likely means that any increase in the defense spending caps must be paired with an equal increase in nondefense spending caps. The Bipartisan Budget Acts of 2013 and 2015, for example, saw approximately equal increases in both the defense and nondefense budget caps as Democrats controlled the Senate and Republicans held the House. Yet BBA 2018 led to a greater increase in the defense caps given GOP control of both houses of Congress and the White House. In all three cases, OCO funding was used to significantly boost defense funding (and to a lesser extent nondefense funding) given its exemptions from the caps.

Figure 2. Comparison of Spending Cap Increases in Previous Budget Agreements*

*OCO does not include emergency requirements or disaster relief funding. FY 2019 nondefense OCO value is based on the conference report for the FY 2019 State, Foreign Operations, and Related Programs Appropriations Bill that is yet to be passed by Congress.

For an administration seemingly focused on reducing a federal deficit approaching $1 trillion, increasing discretionary spending by approximately $540 billion over the next two years would appear to be a non-starter. Meanwhile, congressional leaders in the two chambers already appear at loggerheads, with SASC Chairman Jim Inhofe (R-OK) calling for an exemption of BCA spending limits on only defense spending while likely HASC Chairman Adam Smith (D-WA) has signaled greater scrutiny on the defense budget.

In attempting to pass a budget deal, the ultimate goal for the administration, Democrats, and Republicans is to increase the budget caps above their current levels and avoid triggering sequestration. Following through with the plan to return all enduring OCO costs in the base budget in the FY 2020 budget request could risk stalemating negotiations for an agreement. This does not mean that DoD must or should scrap the plan completely. The Department could gradually transition enduring costs out of OCO over the next two years. Ultimately, discretionary spending is only limited by the caps for two more years at which point the distinction between OCO and the base budget will no longer be of such significance. And if the administration is determined to increase the transparency of war funding, it can take the unprecedented step of detailing which OCO accounts rightly support operations abroad and which are enduring costs.

Moving all of OCO’s enduring costs into the base defense budget for the final two years of the Budget Control Act spending limits may not be politically expedient for passing a budget agreement. However, that does not mean that DoD should forgo initiatives to increase accountability, transparency, and efficiency.

[1] For more on enduring costs in the OCO budget, see Todd Harrison’s “The Enduring Dilemma of Overseas Contingency Operations Funding.”

(U.S. Marine Corps photo by Sgt. Katelyn Hunter)